Chanchal Cabrera // August 2019

The microbiome of the human body, the vast array of yeasts and bacteria, archaea, viruses and eukaryotes that co-inhabit our bodies, play a vital role in health and disease, with notable influence on many human illnesses in recent years, including cardiovascular and neurologic diseases, as well as cancer.

Research at King’s College London includes studies of diabetes, obesity, allergy and inflammatory diseases like colitis and arthritis, showing patients with the best outcomes had the richest and most diverse communities of gut microbes. Studies also demonstrate that babies born via caesarean section miss out on some of the microbes they would obtain through a vaginal birth, which may make them more vulnerable to obesity, allergies and asthma.

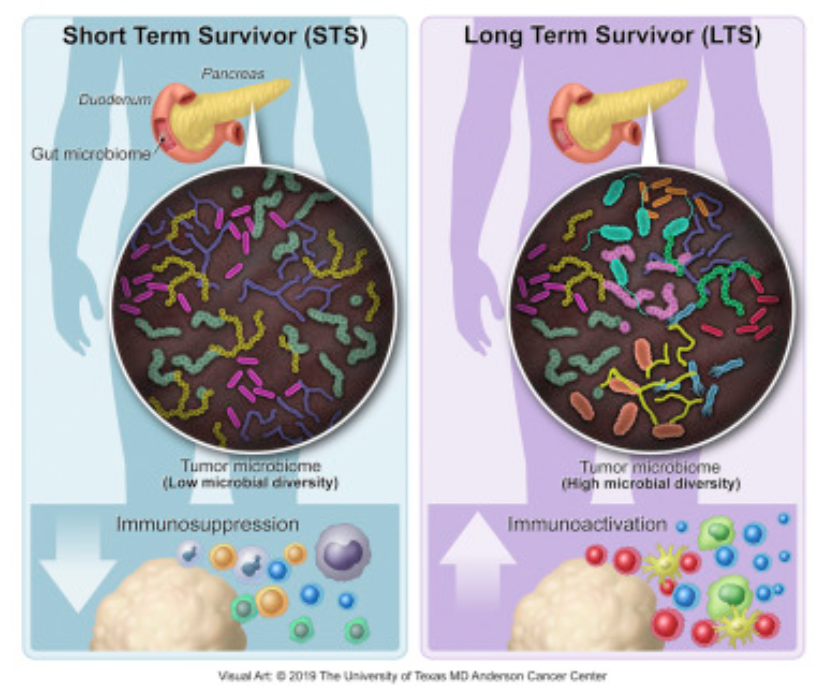

Another report recently published outlines research conducted at MD Anderson and Johns Hopkins hospitals in the US, showing how the tumor microbiome found in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC) influences overall prognosis. Apparently bacteria colonizing the actual cancerous tissue can modulate its biologic behavior and potentially promote immune response to the malignancy. The research shows that a higher diversity of colonizing bacterial species and a specific bacterial profile or range were associated with better outcomes. In addition, they showed that fecal transplants from patients with PDAC were able to modulate the growth of tumor xenografts in mice. The gut microbiome of long-term survivors of PDAC induced a much slower growth of these xenografted cancers compared with fecal transplants from short-term survivors.

Although the researchers stop short of making recommendations based on the evidence, saying only that their study demonstrated that “PDAC microbiome composition, which cross-talks to the gut microbiome, influences the host immune response and natural history of the disease”, it would seem prudent as clinicians to work towards optimal microbiome composition.

Optimizing your microbiome

Of course, this begs the question of actually how to do that? There are estimated to be upwards of 1200 different strains of yeast and bacteria in the lower bowel alone. Currently it is possible to test for somewhere between 12 and 20 of these with varying degrees of reliability, and there are supplements available to purchase with anywhere from 2 or 3 up to 6 or 8 different strains of bacteria and or beneficial yeasts. Clearly this is quite inadequate to make clinical diagnosis or recommendations of any specific probiotic mixes.

In my practice where I am often dealing with chronic conditions, including autoimmunity, inflammatory conditions and, especially cancer, I often find it is more effective to use prebiotics, which are those foods and supplements that actually feed or promote the supposedly “active” or “optimal” microbiota. At the very least, I do encourage patients to eat a wide array of fruits and vegetables, including a good proportion raw, and often to take specific prebiotic agents as well, such as flaxseed, Jerusalem artichokes (sunchokes), and onions or garlic.

Not everybody does well with this diet plan. Some people have such disordered microbiome (dysbiosis) that they cannot tolerate this level of fiber and fermentation all at once. They may need to very diligently and conscientiously avoid all these foods for some 4 to 8 weeks to rest the system, and revert to a baseline level of irritation and inflammation. After that they may be able to introduce these foods slowly, building up a tolerance, and restoring the optimal microbiome in this way.

I also encourage people to eat plenty of fermented foods containing live microbes. Good choices are unsweetened yoghurt; kefir, (a sour milk drink); raw milk cheeses; sauerkraut; kimchi, and fermented soybean-based products such as soy sauce, tempeh and natto.

Slippery Elm, Marshmallow, Licorice and Psyllium are all herbs which contain fermentable sugars which can feed, nourish and regulate the bacterial profile in the digestive tract. This is certainly in part how they are so effective in soothing and healing inflammatory bowel disease. This is not just a function of the mucilage, the complex polysaccharides which absorb water, hold water, soften and bulk up the stool and promote proper peristalsis (defaecation), but also a function of improved gut flora profile using the plant sugars as prebiotics.

Other things that have been shown to improve the diversity and richness of the communities within and upon us, include being around pets and animals, being outside especially with your hands in the dirt, gardening, getting muddy, and eating a wide range of different and varying foods.

Further reading:

- https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/how-to-boost-your-microbiome/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d42473-019-00005-x

- https://www.practiceupdate.com/c/88006/1/1/?elsca1=emc_enews_expert-

insight&elsca2=email&elsca3=practiceupdate_onc&elsca4=oncology&elsca5=newsletter&rid=MTA1MDEyMTE5N

DY5S0&lid=10332481

Cell, Volume 178, ISSUE 4, August 08, 2019

Tumor Microbiome Diversity and Composition Influence Pancreatic Cancer Outcomes Erick Riquelme et al

Most patients diagnosed with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) survive less than 5 years, but a minor subset survives longer. Here, we dissect the role of the tumor microbiota and the immune system in influencing long-term survival. Using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, we analyzed the tumor microbiome composition in PDAC patients with short-term survival (STS) and long-term survival (LTS). We found higher alpha-diversity in the tumor microbiome of LTS patients and identified an intra-tumoral microbiome signature (Pseudoxanthomonas-Streptomyces-Saccharopolyspora-Bacillus clausii) highly predictive of long- term survivorship in both discovery and validation cohorts. Through human-into-mice fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) experiments from STS, LTS, or control donors, we were able to differentially modulate the tumor microbiome and affect tumor growth as well as tumor immune infiltration. Our study demonstrates that PDAC microbiome composition, which cross-talks to the gut microbiome, influences the host immune response and natural history of the disease.